For 20th century history buffs and the like, the bridge over the River Kwai still stands in a corner of Kanchanaburi province, a place not far from Bangkok and a historic site to visit while on an extended stay in Thailand.

Notorious because of the novel by Pierre Boulle and later the film “The Bridge over the River Kwai” starring Alec Guinness and William Holden, among others, the ‘Death Railway’ as it’s been baptized, is a reality that still haunts many of the aging multi nationals that returned to the site of the Bridge to participate in a Remembrance Day in February 1976, thirty years after the end of WWII.

Walking across the bridge in a symbolic gesture of reconciliation with their captors was a difficult accomplishment even three decades after the fighting. Japanese soldiers formerly assigned to the ‘death bridge’ camp came to wipe away old hostilities, but for some POW's it brought multifaceted feelings.

Construction on the wooden bridge, the ‘Railway of Death’, began in early 1942. Built and assembled by prisoners of war, it was destroyed by American bomber planes before the conflict ended in 1945. The bridge was masterminded by the Japanese as part of the 415 kilometers (roughly 260 miles) of rail road track between Bangkok and Rangoon.

The notorious prisoner-of-war camp ran by the occupying Japanese Imperial Army used the forced labor of 30,000 prisoners of war and more than 100,000 slave laborers from all over South East Asia to construct a railway that would link Thailand to Burma.

For the length of almost two years, they were starved as they worked continually to put together the infamous Thai - Burma railroad project.

Initially, Japanese army engineers had projected the railroad would take at least three years to build, however, prison campsite officials at Kanchanaburi, forced laboring prisoners to complete it in eighteen months. For POW work forces, it was a treacherous and wearing undertaking as tracks that followed the length of cliffs had to be built for long distances, and a ledge carved out of the rock in order to shape a foundation and embankment for the construction.

By the end of 1943, when the ‘Railway of Death’ was completed, the Japanese were able to move daily ammunition and supplies to its military camps in Burma without the dangers of transporting provisions by sea. The bridge was subject to frequent air raids between January and June 1945 and POW labor was used to repair it on each occasion.

For 20th century history buffs and the like, the bridge over the River Kwai still stands in a corner of Kanchanaburi province, a place not far from Bangkok and a historic site to visit while on an extended stay in Thailand.

Notorious because of the novel by Pierre Boulle and later the film “The Bridge over the River Kwai” starring Alec Guinness and William Holden, among others, the ‘Death Railway’ as it’s been baptized, is a reality that still haunts many of the aging multi nationals that returned to the site of the Bridge to participate in a Remembrance Day in February 1976, thirty years after the end of WWII.

Walking across the bridge in a symbolic gesture of reconciliation with their captors was a difficult accomplishment even three decades after the fighting. Japanese soldiers formerly assigned to the ‘death bridge’ camp came to wipe away old hostilities, but for some POW's it brought multifaceted feelings.

Construction on the wooden bridge, the ‘Railway of Death’, began in early 1942. Built and assembled by prisoners of war, it was destroyed by American bomber planes before the conflict ended in 1945. The bridge was masterminded by the Japanese as part of the 415 kilometers (roughly 260 miles) of rail road track between Bangkok and Rangoon.

The notorious prisoner-of-war camp ran by the occupying Japanese Imperial Army used the forced labor of 30,000 prisoners of war and more than 100,000 slave laborers from all over South East Asia to construct a railway that would link Thailand to Burma.

For the length of almost two years, they were starved as they worked continually to put together the infamous Thai - Burma railroad project.

Initially, Japanese army engineers had projected the railroad would take at least three years to build, however, prison campsite officials at Kanchanaburi, forced laboring prisoners to complete it in eighteen months. For POW work forces, it was a treacherous and wearing undertaking as tracks that followed the length of cliffs had to be built for long distances, and a ledge carved out of the rock in order to shape a foundation and embankment for the construction.

By the end of 1943, when the ‘Railway of Death’ was completed, the Japanese were able to move daily ammunition and supplies to its military camps in Burma without the dangers of transporting provisions by sea. The bridge was subject to frequent air raids between January and June 1945 and POW labor was used to repair it on each occasion.

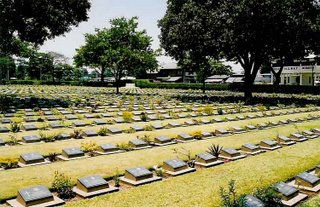

Because of the terrible living and working conditions, limited water and food supply, along with brutal treatment received from their Japanese captors, more than 100,000 people died building the Thai - Burma railway line. Most of the victims were from South East Asia, captured by the Japanese and forced into hard labor. Another 15,000 casualties were Allied POWs; mostly British, Australians, Dutch and a handful of Americans. I read recently, that the ‘Railway of Death’ left in its track, as many deaths as number of wooden sleepers supporting the tracks themselves. At the end of the war the British Army dismantled two and a half miles of track at the Thai-Burma border; the remaining Thai length of the railroad, some 186 miles was handed over to the State Railway of Thailand. Since then, the railroad has been upgraded and is operational and passenger trains of The State Railways of Thailand still run over part of the Burma-Siam -- as it is called now -- 'Death Railway' from Bangkok and over the River Kwai Bridge to the line's current terminus at Nam Tok. In 1946 a ‘War Graves Commission’ survey party whose task was to locate POW cemeteries and grave sites along the Burma-Thailand railway took the opportunity to recover equipment and documents which had been secretly buried, by the Japanese in the graves of deceased POWs. Temporary wooden crosses on the graves of Allied soldiers were scattered over two make-shift cemeteries, one with 1,500 graves and one with 168 graves. Some of the allied countries involved exhumed and reburied their nationals’ bodies in the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery towards the end of 1945.

The Kanchanabury War Cemetery, in sight of the Bridge, holds thousands of POWs who died while building it. The plot is sectioned according to nationality, and provides a quiet, green grassed and treed moving tribute to those who lost their lives defending their lands. Directly across the street is a museum that details the years of suffering in the 1940’s. The museum presents a replica of the bamboo huts used to house the prisoners of war. There is an on-going black and white film with actual footage taken by the Japanese, and the whole place is imbued with the whistling sounds of the popular “Bridge over the River Kwai” tune, popularized in the film. Photographs, paintings and news clips with interviews immediately following the end of the war and loads of memorabilia line the museum walls. At one end of the bridge, on the southern bank of the River Kwai, there’s a memorial plaque commemorating the historic occurrence. The inscription on the plaque placed in 1973 reads: “Thai-Burma Railway Line”. In about 500 words, it chronicles the tragic events that unfolded between the years 1942 and 1945. Edie Wilcox 12/05